Of everything in the Harry Potter universe, I must admit I find the wands most fascinating. Not just because they play an integral part of spell casting – they also reflect the unique personalities of their owners. Additionally, shouting in Latin is so much more exciting when waving a wand. We tried to capture a little of that magic at Wand Works, our Harry Potter event.

Of everything in the Harry Potter universe, I must admit I find the wands most fascinating. Not just because they play an integral part of spell casting – they also reflect the unique personalities of their owners. Additionally, shouting in Latin is so much more exciting when waving a wand. We tried to capture a little of that magic at Wand Works, our Harry Potter event.

Originally, the event was just going to be about wands, wand making, and wand testing. But then I started thinking about the other ways students prepare for Hogwarts. So we brought book bags, text books, and owls into the mix. And, while I’ve recreated an assortment of Hogwarts classes over the years (check out this boggart from Defense Against the Dark Arts), I’ve never managed to do Muggle Studies. We had to do something on Muggle Studies!

Originally, the event was just going to be about wands, wand making, and wand testing. But then I started thinking about the other ways students prepare for Hogwarts. So we brought book bags, text books, and owls into the mix. And, while I’ve recreated an assortment of Hogwarts classes over the years (check out this boggart from Defense Against the Dark Arts), I’ve never managed to do Muggle Studies. We had to do something on Muggle Studies!

Here’s how our event worked. As kids entered the library, they were greeted by a table full of these awesome book bags:

That beautiful Accio Books logo was designed by Polly Carlson. You can find it here, on her truly clever blog Pieces by Polly. She was kind enough to give us permission to use it for the event. Also at the table were a slew of Crayola metallic markers for bag customization:

That beautiful Accio Books logo was designed by Polly Carlson. You can find it here, on her truly clever blog Pieces by Polly. She was kind enough to give us permission to use it for the event. Also at the table were a slew of Crayola metallic markers for bag customization:

Those are 13.5″ x 14.5″ polypropylene totes from 4Imprint. Specifically, it’s the “Value Polypropylene Tote (item #103873). We tested a couple of polypropylene bags for this project, and 4Imprint’s held the Crayola metallic markers ink beautifully (it smeared on the others). Also, 4Imprint had the best prices and customer service, flat out.

Those are 13.5″ x 14.5″ polypropylene totes from 4Imprint. Specifically, it’s the “Value Polypropylene Tote (item #103873). We tested a couple of polypropylene bags for this project, and 4Imprint’s held the Crayola metallic markers ink beautifully (it smeared on the others). Also, 4Imprint had the best prices and customer service, flat out.

Tucked inside each and every event bag was a color ticket, which lead the lucky witch or wizard to my favorite fictitious bookstore of all time:

Here’s our Flourish & Blotts, staffed by Princeton junior Gabrielle Chen (she’s also the artist behind that fantastic sign)!

Here’s our Flourish & Blotts, staffed by Princeton junior Gabrielle Chen (she’s also the artist behind that fantastic sign)!

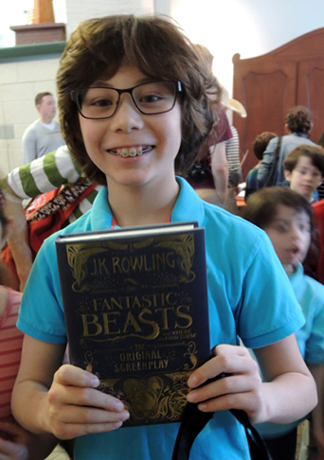

Behind Gabrielle was a shelf stocked with copies of The Tales of Beedle the Bard, Quidditch Through the Ages, Hogwarts: A Cinematic Yearbook, and the Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them screenplay (alas, we missed the release of the text book version of Fantastic Beasts by mere weeks). There were also real quill pens with powdered ink packets, and some adorable Harry Potter Magical Creatures coloring kits.

Behind Gabrielle was a shelf stocked with copies of The Tales of Beedle the Bard, Quidditch Through the Ages, Hogwarts: A Cinematic Yearbook, and the Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them screenplay (alas, we missed the release of the text book version of Fantastic Beasts by mere weeks). There were also real quill pens with powdered ink packets, and some adorable Harry Potter Magical Creatures coloring kits.

The tickets were color-coded with items on the shelves. Hand in your ticket, and receive the matching item! Just in case you’re wondering, we did sort and distribute the event bags by estimated age of the child. This was to insure that a 4 year-old received a Harry Potter coloring kit, not a copy of Fantastic Beasts.

The tickets were color-coded with items on the shelves. Hand in your ticket, and receive the matching item! Just in case you’re wondering, we did sort and distribute the event bags by estimated age of the child. This was to insure that a 4 year-old received a Harry Potter coloring kit, not a copy of Fantastic Beasts.

Did you notice the little cauldron with the brooms sticking out of it in the above photo? Since we couldn’t buy books, quills, and coloring kits for everyone, the little brooms were the prize most frequently received by kids of all ages. But they are way cool because they are actually customized broom pens!

These are “Personalized Witch’s Broom Pens” from Oriental Trading Company ($12 a dozen). For no extra fee, you can customize them with 1 line of text up to 16 characters in length. We went with “Nimbus 2000.” Everyone LOVED them! In fact, the whole table was a lot of fun. It was terrific to see kids, holding books (or quills, or coloring kits, or broom pens) with big grins on their faces.

These are “Personalized Witch’s Broom Pens” from Oriental Trading Company ($12 a dozen). For no extra fee, you can customize them with 1 line of text up to 16 characters in length. We went with “Nimbus 2000.” Everyone LOVED them! In fact, the whole table was a lot of fun. It was terrific to see kids, holding books (or quills, or coloring kits, or broom pens) with big grins on their faces.

Elsewhere on the event floor was real-life wandmaker Lane O’Neil from Gray Magic Woodworking. You previously met Lane in this post. In person, his wands are even more beautiful, fantastic, and magical. His table was so swarmed. I couldn’t even get near it for the first hour of the event!

Elsewhere on the event floor was real-life wandmaker Lane O’Neil from Gray Magic Woodworking. You previously met Lane in this post. In person, his wands are even more beautiful, fantastic, and magical. His table was so swarmed. I couldn’t even get near it for the first hour of the event!

Lane also displayed his lathe, tools, different types of wood, and wands in different stages of completion. He did demonstrations, showed slides, and answered questions throughout the entire event.

Lane also displayed his lathe, tools, different types of wood, and wands in different stages of completion. He did demonstrations, showed slides, and answered questions throughout the entire event.

Not far from Lane was our Muggle Artifact exhibit, curated by Princeton University sophomore Téa Wimer. The exhibit consisted of 45 Muggle objects complete with informative exhibit labels. Below, two attendees ponder a Cookie Slicer (which, amazingly, looks just like an old school photo enlarger).

Not far from Lane was our Muggle Artifact exhibit, curated by Princeton University sophomore Téa Wimer. The exhibit consisted of 45 Muggle objects complete with informative exhibit labels. Below, two attendees ponder a Cookie Slicer (which, amazingly, looks just like an old school photo enlarger).

And here, two scholars consider a World Checker. Nearby is a rather puzzling object on a pedestal. Kids could write guesses as to what the Muggles use the object for. The full exhibit, as well as an interview with Curator Téa Wimer, is now online!

And here, two scholars consider a World Checker. Nearby is a rather puzzling object on a pedestal. Kids could write guesses as to what the Muggles use the object for. The full exhibit, as well as an interview with Curator Téa Wimer, is now online!

Owls are another must for Hogwarts students, so we had a table where kids could make these awesome and super simple wrist owls.

Owls are another must for Hogwarts students, so we had a table where kids could make these awesome and super simple wrist owls.

And now we come to the main event – THE WANDS. After much searching and testing, we settled on wands made from cooking chopsticks, hot glue, and paint. They are, in fact, very much like the wands our kid tester made for her DIY Harry Potter party.

And now we come to the main event – THE WANDS. After much searching and testing, we settled on wands made from cooking chopsticks, hot glue, and paint. They are, in fact, very much like the wands our kid tester made for her DIY Harry Potter party.

But there were problems. While these types of wands are wonderful in small batches, we needed hundreds. The event was recommended for kids ages 5-11. Would someone poke their eye out? Hot glue is used to create the texture of the wand. Would someone burn their fingers? The wands require paint. Would they dry sufficiently? And – how messy was this all going to get?

Turns out, we solved all these problems, and everything went beautifully.

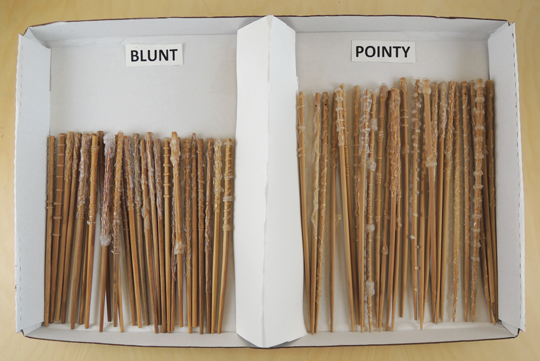

First, we bought 2 kinds of cooking chopsticks on Amazon. 13″ pointy ones (4 pairs cost $7.40) and 10.5″ blunt ones (10 pairs cost $11). If you’d like to know the exact brands we used, e-mail me for the links.

For the event, we made trays out of box lids, separating the wands into blunt and pointy sections. This was primarily for the benefit of parents and caretakers. The pointy chopsticks were definitely the most popular, but we also had many adults who were very grateful for the blunt wands. There was even some quietly-switch-from-pointy-to-blunt-while-the-kid-is-distracted going on.

For the event, we made trays out of box lids, separating the wands into blunt and pointy sections. This was primarily for the benefit of parents and caretakers. The pointy chopsticks were definitely the most popular, but we also had many adults who were very grateful for the blunt wands. There was even some quietly-switch-from-pointy-to-blunt-while-the-kid-is-distracted going on.

Next came the hot glue. While we would have loved for kids to make their own hot glue designs at the event, we knew that just wasn’t possible on a large scale. So we hot glued all the wands in advance. It took us a couple months of chipping away here and there, but in the end we had hundreds of wands, and no two were alike.

Next came the hot glue. While we would have loved for kids to make their own hot glue designs at the event, we knew that just wasn’t possible on a large scale. So we hot glued all the wands in advance. It took us a couple months of chipping away here and there, but in the end we had hundreds of wands, and no two were alike.

Next, the paint! After testing a number of different paints, we settled on Michaels Craft’s in-store brand, CraftSmart. We used their satin acrylic paint because it was water-based, non-toxic, fast-drying, and there were lots of different shades of brown. The regular acrylic paint was too dull, but the satin left a really nice finish on the wand.

Next, the paint! After testing a number of different paints, we settled on Michaels Craft’s in-store brand, CraftSmart. We used their satin acrylic paint because it was water-based, non-toxic, fast-drying, and there were lots of different shades of brown. The regular acrylic paint was too dull, but the satin left a really nice finish on the wand.

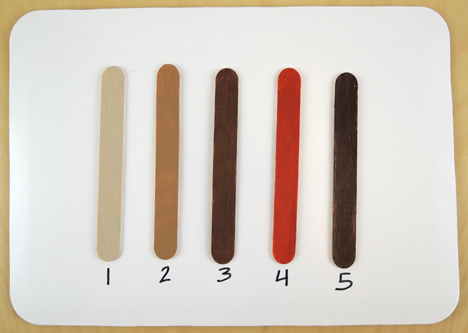

At the event, kids selected the wand they liked from the tray, and then picked the paint color they wanted. To make the color selection easier, we made several paint choice panels out of cake pads and jumbo craft sticks. The numbers below the paint samples corresponded to the name of the colors (which were written on the back of the panel for the table staff).

At the event, kids selected the wand they liked from the tray, and then picked the paint color they wanted. To make the color selection easier, we made several paint choice panels out of cake pads and jumbo craft sticks. The numbers below the paint samples corresponded to the name of the colors (which were written on the back of the panel for the table staff).

From left to right, the CraftSmart satin acrylic paint colors are khaki, golden brown, brown, burnt orange, and espresso. Burnt orange and espresso were definitely the most popular. But all the colors looked fantastic.

From left to right, the CraftSmart satin acrylic paint colors are khaki, golden brown, brown, burnt orange, and espresso. Burnt orange and espresso were definitely the most popular. But all the colors looked fantastic.

You need very little paint per wand. To keep the mess down and conserve paint, we gave each kid a 1.25oz plastic cup with a little bit of paint inside it, a paint brush, and a paper plate to work on. When the kid finished, his/her paint cup and brush could be used with another kid.

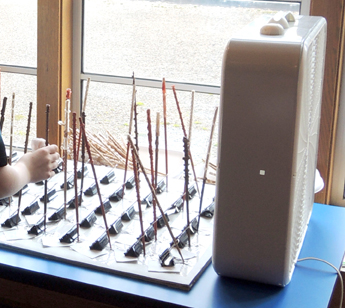

This paint was extremely fast drying on the wood, even with multiple coats. The hot glue, however, was another story. In order to dry the wands faster, we put together a wand-drying chamber out of a piece of cardboard, jumbo binder clips held down with packing tape, and 2 box fans running on low.

This paint was extremely fast drying on the wood, even with multiple coats. The hot glue, however, was another story. In order to dry the wands faster, we put together a wand-drying chamber out of a piece of cardboard, jumbo binder clips held down with packing tape, and 2 box fans running on low.

Below you can see the wand drying chamber in action, with the wands inserted in the clips. At the event, kids wrote their names on little bits of paper, which were clipped with the corresponding wands. Depending on how many coats of paint were on the wand, it typically took 5 – 10 minutes for a wand to dry in the chamber (15 if there was a LOT of paint).

Below you can see the wand drying chamber in action, with the wands inserted in the clips. At the event, kids wrote their names on little bits of paper, which were clipped with the corresponding wands. Depending on how many coats of paint were on the wand, it typically took 5 – 10 minutes for a wand to dry in the chamber (15 if there was a LOT of paint).

To be clear – the wand drying chamber was tucked behind the event tables, away from the crowds. Only event staff had access to it for obvious reasons. However, if I was to do this event again, I would definitely add a designated “Wand Pick-Up Area” to make things run even more smoothly.

To be clear – the wand drying chamber was tucked behind the event tables, away from the crowds. Only event staff had access to it for obvious reasons. However, if I was to do this event again, I would definitely add a designated “Wand Pick-Up Area” to make things run even more smoothly.

FINALLY, we had an activity that I only dared dream of, but Princeton University junior José M Rico made a reality. A virtual, interactive, wand-testing classroom. It was AMAZING. here’s a photo of Katie casting one mean Bombarda spell.

All the details of the game, as well as video and a free download, can be found here!

All the details of the game, as well as video and a free download, can be found here!

I’d like to thank everyone who made this event possible. Thank you Polly Carlson for graciously letting us use your Accio Wand design, student artist Gabrielle Chen for painting the awesome Flourish & Blotts sign, and Lane O’Neil for bringing his talent and wands to the event. A hearty round of applause to our incredibly creative Muggle Artifacts Curator Téa Wimer. Further applause to our wildly talented game designer Jose Rico, as well as artist Jeremy Gonclaves, who allowed us to his 3D game background.

A big shout out to our extensive team of wand hot gluers, Andrea Immel for swooping in to help at our owl table, and all the Princeton University students who volunteered their time to help at the event. Many, many thanks!

Does the wizard choose the wand? Or does the wand choose the wizard?

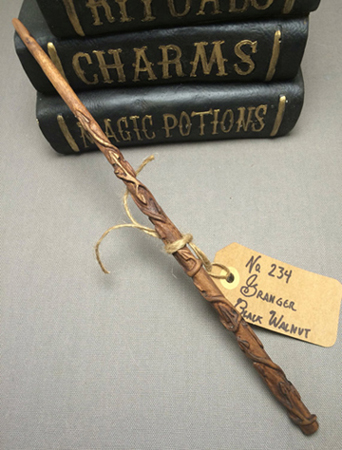

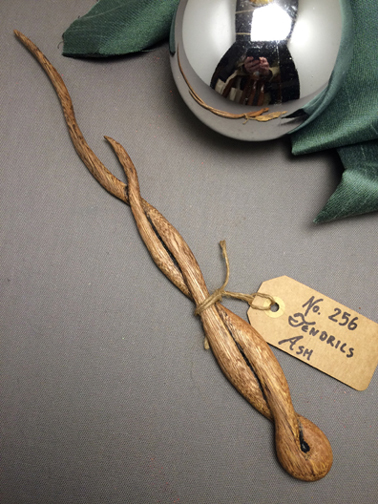

Does the wizard choose the wand? Or does the wand choose the wizard? Fantastically, Lane donated 3 of his wands to our Accio Wand blog contest! Readers of all ages were invited to submit an original Harry Potter spell, be it silly or serious. The winning entries are posted

Fantastically, Lane donated 3 of his wands to our Accio Wand blog contest! Readers of all ages were invited to submit an original Harry Potter spell, be it silly or serious. The winning entries are posted  What sorts of woods do you use?

What sorts of woods do you use? Where do you acquire the wood for your wands?

Where do you acquire the wood for your wands? My favorite place is called Hearn, they are located in Oxford, PA. It’s like a candy store for people who craft wood. They have everything from domestic scraps to 16′ slabs of exotic wood shipped from the hearts of far away continents.

My favorite place is called Hearn, they are located in Oxford, PA. It’s like a candy store for people who craft wood. They have everything from domestic scraps to 16′ slabs of exotic wood shipped from the hearts of far away continents. When it’s just about fully shaped, I use sandpaper to smooth it – working to smaller grits until I’m happy with the texture. I can also stain or paint the wand while it’s spinning. I usually use a carnauba wax/ tung oil blend to finish fully.

When it’s just about fully shaped, I use sandpaper to smooth it – working to smaller grits until I’m happy with the texture. I can also stain or paint the wand while it’s spinning. I usually use a carnauba wax/ tung oil blend to finish fully. When I’m just about done, I “part” the wand from the lathe by cutting the material away by the tip or pommel until the wand falls off. I move the piece to the work bench, saw the remaining scrap block off, sand the two rough ends, and finish with carving, wood burning, or other decorations. I tag it, give it a name, and a number.

When I’m just about done, I “part” the wand from the lathe by cutting the material away by the tip or pommel until the wand falls off. I move the piece to the work bench, saw the remaining scrap block off, sand the two rough ends, and finish with carving, wood burning, or other decorations. I tag it, give it a name, and a number. How long does it take to make a wand?

How long does it take to make a wand? What locations have your wands shipped to?

What locations have your wands shipped to? What’s the most unusual or significant wand you’ve ever made?

What’s the most unusual or significant wand you’ve ever made? The most significant wand I’ve ever made is a tie. I made a Beech wand that was chosen by a young girl from the Make-A-Wish Foundation. There wasn’t anything too special about it other than the leather wrapped handle, but she chose it.

The most significant wand I’ve ever made is a tie. I made a Beech wand that was chosen by a young girl from the Make-A-Wish Foundation. There wasn’t anything too special about it other than the leather wrapped handle, but she chose it. The other one was purchased by a mother in London, England. She bought a Japanese Maple for her son Harry for his 10th birthday…that was pretty cool. His mother sent me a photo.

The other one was purchased by a mother in London, England. She bought a Japanese Maple for her son Harry for his 10th birthday…that was pretty cool. His mother sent me a photo.

It’s a mysterious bottle filled with a unique, glowing essence. What could the essence be? Happiness? Triumph? Panache? The Thrill of Your First Ride on the Back of an Arachnimammoth? This radiant project was part of

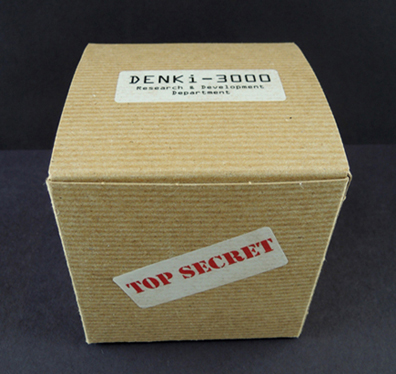

It’s a mysterious bottle filled with a unique, glowing essence. What could the essence be? Happiness? Triumph? Panache? The Thrill of Your First Ride on the Back of an Arachnimammoth? This radiant project was part of  But, because DENKi-3000’s research and development department is shrouded in secret, the entire project came as a take-home kit with strict instructions to NOT open the box until you get home.

But, because DENKi-3000’s research and development department is shrouded in secret, the entire project came as a take-home kit with strict instructions to NOT open the box until you get home. You’ll need:

You’ll need: First, the bottle! We used 2.25″ screw-top jars scored from the wedding section of Michaels craft store. 20 jars cost $21, but we had a 40% off coupon. Woot! To make it look less like a spice jar, we hot glued a clear

First, the bottle! We used 2.25″ screw-top jars scored from the wedding section of Michaels craft store. 20 jars cost $21, but we had a 40% off coupon. Woot! To make it look less like a spice jar, we hot glued a clear

The glow glue goes on opaque, but as you can see below, it dries semi-transparent. Glow-in-the-dark paint (which we found in the t-shirt decorating section of Michaels) also dries transparent:

The glow glue goes on opaque, but as you can see below, it dries semi-transparent. Glow-in-the-dark paint (which we found in the t-shirt decorating section of Michaels) also dries transparent: The glow glue, however, glows much stronger. Perhaps because you can control the ratio of pigment to glue? But the paint is glowing. And it requires a lot less measuring and mixing. So you can’t go wrong with either choice.

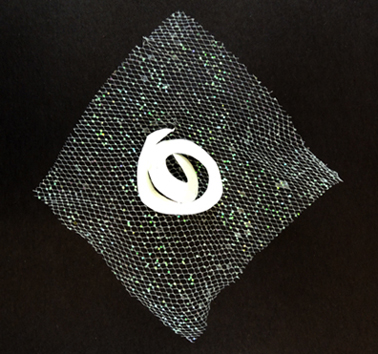

The glow glue, however, glows much stronger. Perhaps because you can control the ratio of pigment to glue? But the paint is glowing. And it requires a lot less measuring and mixing. So you can’t go wrong with either choice. It’s time to create your creature essence! This is basically a card stock shape wrapped in tulle. Since we wanted the bottles to also look pretty in daylight, we went with glitter tulle, which you can find in the ribbon section of Michaels.

It’s time to create your creature essence! This is basically a card stock shape wrapped in tulle. Since we wanted the bottles to also look pretty in daylight, we went with glitter tulle, which you can find in the ribbon section of Michaels. Once the bottle, the shape, and the tulle are dry, gently wrap the tulle around the shape and tuck it into the bottle. Screw the lid on, write the name of your essence on a label, and attach the label to the bottle. We used 1.25″ price tags with elastic strings, found it the beading section at Michaels. We found the plastic baggies for the pigment there too. Both of these things cost just a few bucks.

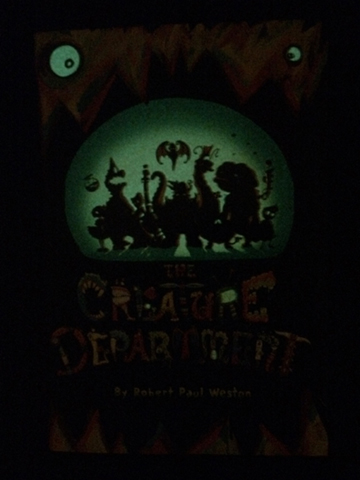

Once the bottle, the shape, and the tulle are dry, gently wrap the tulle around the shape and tuck it into the bottle. Screw the lid on, write the name of your essence on a label, and attach the label to the bottle. We used 1.25″ price tags with elastic strings, found it the beading section at Michaels. We found the plastic baggies for the pigment there too. Both of these things cost just a few bucks. Every story time, without fail, the kids would ask to see the cover glow. No matter how many times we looked, they never lost their enthusiasm for it. In the video below, you can’t see the book, but you can definitely hear the kids reacting to its cover!

Every story time, without fail, the kids would ask to see the cover glow. No matter how many times we looked, they never lost their enthusiasm for it. In the video below, you can’t see the book, but you can definitely hear the kids reacting to its cover!