From Love Inc.

Remember when this dress premiered on the Eras Tour? We do! The custom Vivienne Westwood gown is filled with the lyrics from Track 10 of Tay’s 2024 album, The Tortured Poets Department. It inspired us to seek out more artists and designers who took literary fashion to the next level. So today we present Pop’s Top 10 literary gowns!

#1 GONNA BE GOLDEN

From Shelf Talker

Created by Ryan Jude Novelline, the artist stitched together the colorful illustrations from discarded Little Golden Books, and fashioned a bodice from the spines. If you’d like to read an interview about his amazing creation, please follow this link.

From The Literary Rapport

#2 BOOK WITCH

From Reddit

Posted on Reddit, the detailing on this dress is off the charts! Plus, the hat! The HAT.

#3 SUPER SEUSS

From Bored Panda

Created by Rebecca Humes, the Seuss-specific shredded tutu and bouncy book characters on springs is delightfully whimsical!

#4 DISNEY DANCER

From Bored Panda

Another dress by Rebecca Humes. But this one was created from Disney books and features a skirt composed of thousands of chain links. WOW!

#5 POTTER PROM

From Bored Panda

Hailey Skoch rustled her way to her Arkansas senior prom in a dress made from multiple volumes of Harry Potter books! You can read more about her process here.

#6 FANTASTIC FAIRY

From Ingrid’s Notes

Winner of cutest, most adorable wings and folded tutu is this phenomenal book fairy!

#7 VOLUMINOUS VOLUMES

From Faerie Magazine

This distinct dress with a colonial flare was created by White Knight Cosplay. And just look at that teacup broach!

#8 FAIRY TALE FASHIONISTA

From When I Grow Up

A stack of unwanted volumes transformed into a fairy tale worthy dress by Helen Hobden, who also entered it in a contest judged by Maisie Williams! Read more about her adventure here.

#9 BOUND TO IMPRESS

From For Reading Addicts

French designer Silvie Facon created this flowing masterpiece from old leather spines that had separated from books. It took 250 hours! More more extensive photos, plus more dresses, please follow this link.

#10 SHORT STORY

From For Reading Addicts

Silvie Facon also created this sassy little folded dress, again by only using books that were beyond repair. For more details, please see this link.

Feeling inspired but also maybe a tad overwhelmed by the sheer volume of talent? No worries! You can craft this simple origami newsprint dress by following the instructions here.

Pssst! We also made a Cinderella dress out of highly unusual materials! See that here.

Kids wielded static electricity wands, learned about magnetic levitation, unveiled the Grimmerie’s invisible ink, tested Glinda’s bubble travel potion, and examined the pH levels of popular potions.

Kids wielded static electricity wands, learned about magnetic levitation, unveiled the Grimmerie’s invisible ink, tested Glinda’s bubble travel potion, and examined the pH levels of popular potions.

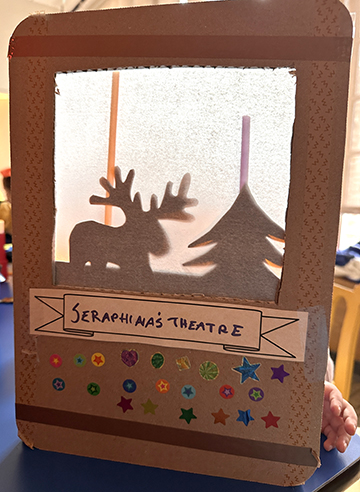

At Seraphina’s theater, there were some distinct holiday vibes happening!

At Seraphina’s theater, there were some distinct holiday vibes happening!