Imagine you are a New York Times best-selling author with 11 books to your name, but no one knows your name? Your real name that is. Or your identity. In fact, your entire career is based on secrets, hiding, and anonymity. And then you decide to do the most amazingly brave thing imaginable. You come out.

Imagine you are a New York Times best-selling author with 11 books to your name, but no one knows your name? Your real name that is. Or your identity. In fact, your entire career is based on secrets, hiding, and anonymity. And then you decide to do the most amazingly brave thing imaginable. You come out.

World, please welcome Raphael Simon, a.k.a. Pseudonymous Bosch.

Simon’s new book, The Anti-Book (Penguin, 2021, illustrated by Ben Scruton), is the first under his own name. It follows the story of Mickey, an angry, unhappy, sensitive, and bullied middle schooler who wants the world to go away. It does. Epically.

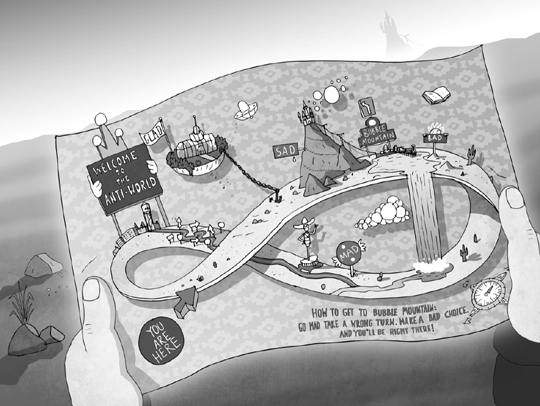

Now Mickey must navigate this way through The Anti-World, which is basically his head wildly flipped, tripped, and turned inside out. It’s also story about identity, family, fear, and acceptance. All told with Simon’s signature irreverence, hilarity, and creativity.

The Anti-Book is an adventure story, but it’s also about identity. When you first conceptualized this book, did you see it as a journey through a fantastical place? Or a journey through identity? Or perhaps both?

At first, I had no idea what kind of journey it would be. For a long time, I was stuck, horribly stuck, at the stage where Mickey makes his world disappear. I had my tornado, so to speak—a magic book that erases anything written in it—but I had no Oz, let alone a yellow brick road to follow. The fantastical elements began to emerge when I decided that the things Mickey erased would reappear in opposite “anti” forms in the Anti-World, the first of these being the flyhouse (housefly in reverse).

But it was only when I started to map the Anti-World over Mickey’s emotions and memories—I was a bit influenced by the Pixar movie Inside Out, in this regard—that I really felt like I’d made a breakthrough. As the emotional dam broke for Mickey, the creative dam broke for me. Mickey is told that he’s gay, that he’s angry, he’s told a lot of things, but it’s only when he learns to identify his feelings for himself that he begins to recover from the trauma he’s experienced. He is still forging his identity when the book ends; the difference is he’s the one forging it.

The book is very personal, and draws from your own experiences as a 12 year-old. Was there a special significance in naming your main characters Mickey and Alice?

Mickey is named after the hero of my favorite picture book of all time: In the Night Kitchen by Maurice Sendak. Like my Mickey, Sendak’s Mickey goes on a fantastical dream-journey that involves giant food items. (Milk and cake batter in the case of Sendak, Chocolate chip cookies in the case of the Anti-Book.) Come to think of it, In the Night Kitchen is also a story about identity. “I’M NOT THE MILK AND THE MILK’S NOT ME,” Sendak’s Mickey declares. “I’M MICKEY!”

Alice’s name also comes from a book about a topsy turvy, inside out adventure. Mickey’s big sister, who becomes his little big sister in the Anti-World, shrinking to the size of Mickey’s finger, is named after perhaps the most famous shrinking protagonist in literature. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has always loomed large in my imagination for reasons I’m not certain I could articulate, but I do remember my high school English teacher going on a furious rant one day about all the students who wrote papers comparing Alice’s rabbit hole adventure to a drug trip. I swear I never wrote a paper like that, but I did later in life claim that all my novels were typed by a rabbit. Make of that what you will.

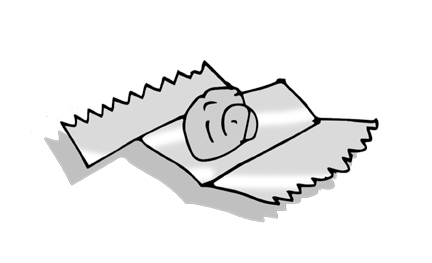

Pink bubble gum plays a huge role in this book. In this case, it has evil associations. Why pink bubble gum?

As you might guess from reading the book, I have a love-hate relationship with bubblegum. I love chewing. I love popping bubbles. But I hate that slightly nauseated, I’m fed-but-not-full feeling that gum gives you. It was partly this feeling that I had in mind when I was writing. At the risk of sounding like the graduate student I once was, I see bubblegum as a metaphor for capitalist consumption: Gum creates a need where there wasn’t one, then fails to fill the need it has created. It’s a self-perpetuating marketing machine.

At the same time, there is a gendered aspect to the way bubblegum is portrayed in American culture. Mickey’s sister’s boyfriend bullies Mickey by telling him that gum is a “girl thing.” “Why ‘cause it’s pink?” Mickey responds. “That’s stupid […] Gum isn’t a girl thing or a guy thing.” Boyfriend: “Oh so it’s gay thing.” Mickey: “Gum isn’t anything. It’s gum!” Obviously, I’m with Mickey on that, but on a subliminal level, I think the pink bubblegum embodies Mickey’s ambivalence about his still-buried sexuality. At the end, when he is closer to openly embracing his queer identity, he gives up the gum chewing.

This story contains lots of wordplay, puns, unusual destinations and strange characters. Do you think you could have written this book, exactly as it is, eleven books ago?

Exactly as it is? No. As you know, there are plenty of puns and strange characters in my early books. In fact, one of the reasons I liked being Pseudonymous Bosch was that I could be as silly as I wanted without feeling self-conscious about it. I hope, however, that I have learned to be simpler and more emotionally direct with time. As wacky as the Anti-World is, I tried to keep Mickey’s story straightforward (not to be confused with straight, of course!) and heartfelt.

Writers sacrifice a lot for their projects – time, energy, mental space. Is there something that this book has given BACK to you?

Yes. My name. It’s Raphael Simon, by the way. Not Pseudonymous Bosch.

In the spirit of the Anti-Book, please tell us five things you couldn’t do without.

Chocolate. I guess I am still Pseudonymous Bosch, after all.

Cheese.

New books.

Old friends.

My family. Well, most of the time.

Intereseted in more interviews with Mr. Bosch-Simon? Click here for a 2011 webcast/podcast, and here for a 2014 blog interview!

Illustrations by Ben Scruton. Images courtesy of Raphael Simon.