December 7th was World Kamishibai Day, and we were honored to invite the amazing Dr. Tara McGowan for a special international story time at our library! While I have performed kamishibai in elementary school classrooms (and blogged about it extensively here) I am no match for the sheer talent of Tara – bilingual kamishibai historian, scholar, and artist extraordinaire!

December 7th was World Kamishibai Day, and we were honored to invite the amazing Dr. Tara McGowan for a special international story time at our library! While I have performed kamishibai in elementary school classrooms (and blogged about it extensively here) I am no match for the sheer talent of Tara – bilingual kamishibai historian, scholar, and artist extraordinaire!

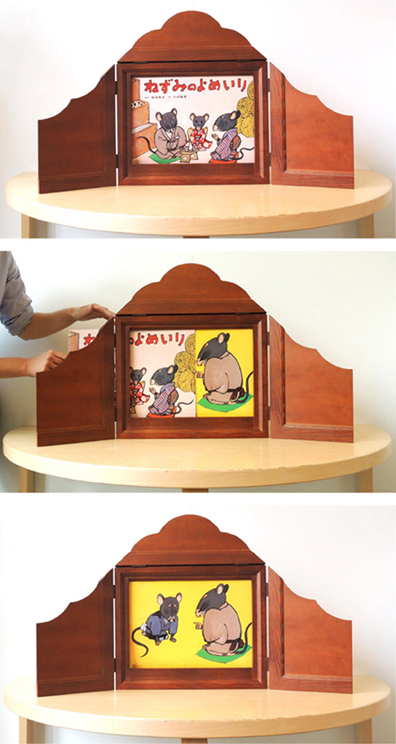

If you don’t have time to jump over my kamishibai post, I’ll quickly summarize: Kamishibai (pronounced kah-me-she-bye) is a form of Japanese storytelling that involves illustrated story cards and a small, portable stage (you can also perform without the stage). While telling the tale, you pull the cards out of the side of the stage to make the story progress.

If you don’t have time to jump over my kamishibai post, I’ll quickly summarize: Kamishibai (pronounced kah-me-she-bye) is a form of Japanese storytelling that involves illustrated story cards and a small, portable stage (you can also perform without the stage). While telling the tale, you pull the cards out of the side of the stage to make the story progress.

It’s colorful, dynamic, simple, and absolutely intended to be enjoyed by an audience. And the art on the cards! Wow! Here is one from The One-Inch Boy:

It’s colorful, dynamic, simple, and absolutely intended to be enjoyed by an audience. And the art on the cards! Wow! Here is one from The One-Inch Boy:

Issun-boshi (The One Inch Boy). Written by Joji Tsubota, illustrated by Hisao Suzuki

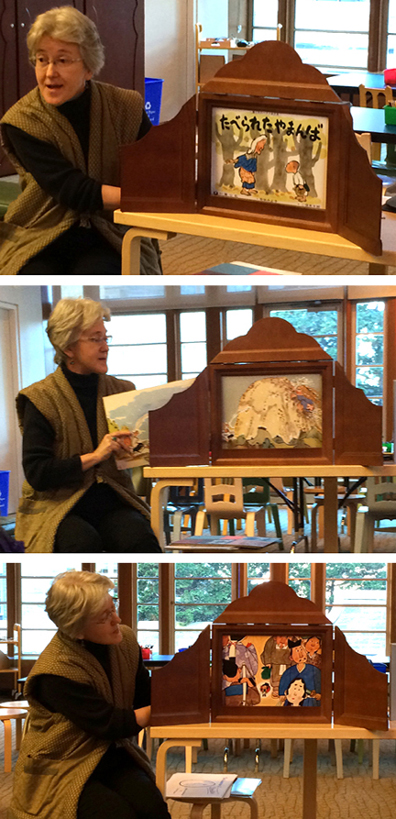

Tara began her story time with a little history. She brought a copy of Allen Say’s book, Kamishibai Man (which Tara wrote the afterword for by the way!) and talked briefly about the evolution of this art form. Then, with a little audience help, she launched into her performance, which consisted of four short kamishibai stories.

It’s difficult to capture the liveliness of a kamishibai performance with photos (and I didn’t want to be obtrusive and shoot a video). But Tara is a MASTER storyteller. Seamlessly mixing Japanese and English, she uses her voice in an incredibly lively way, both to narrate and express sound and motion. She varies the way she pulls to cards to build suspense or depict action, and is in constant communication with her audience.

It’s difficult to capture the liveliness of a kamishibai performance with photos (and I didn’t want to be obtrusive and shoot a video). But Tara is a MASTER storyteller. Seamlessly mixing Japanese and English, she uses her voice in an incredibly lively way, both to narrate and express sound and motion. She varies the way she pulls to cards to build suspense or depict action, and is in constant communication with her audience.

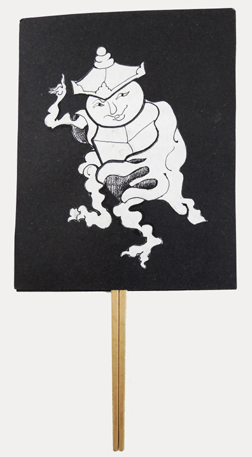

The story time kids also made tachi-e puppets (you’ll find the instructions here).

After story time, I caught up with Tara to chat about her work, and the art of kamishibai:

After story time, I caught up with Tara to chat about her work, and the art of kamishibai:

How long have you been performing kamishibai?

Since 2000, so almost 2 decades now.

Can you tell us a little about its history?

The kind of kamishibai commonly performed today was first introduced to the streets of Japan in 1929. The first street kamishibai of this type were based on films because silent films in Japan almost always had a movie narrator standing next to the screen, providing an oral soundtrack. These movie narrators, known as benshi, were enormously popular, so kamishibai storytellers on the streets tried to emulate their vocal style, while moving the pictures in the stage in tandem with their telling. When sound came to film, many former benshi are said to have turned to kamishibai instead. The puppet style of kamishibai, called tachi-e (standing pictures), began much earlier in the 19th century, inspired by magic-lantern shows. Both kinds of kamishibai were used to sell candy or other treats on the street corners, especially in urban areas.

What do you like about kamishibai storytelling versus other kinds of storytelling?

I started out performing oral storytelling, without props, and I still like oral storytelling best for interacting with an audience and being able to tell more emotionally complex tales. As a performer, I experience the two forms very differently. With oral storytelling, the audience sees their own version of what the storyteller is evoking with his or her words and gestures, but, with kamishibai, the storyteller’s role is to bring the images on the cards to life. The interaction with the audience is less direct because the storyteller and the audience are all focused on the movement of the cards.

When kamishibai illustrations are designed well, they can work magic! But, just like with picture books, there are many poorly designed kamishibai out there. As a visual artist, I find designing my own kamishibai stories to be an ever-stimulating challenge, and it’s great to get immediate feedback from a live audience to know what is working or what needs changing. I also really enjoy working with people of all ages to create and perform their own kamishibai.

You’ve done scores of kamishibai workshops with kids and teens. What’s your experience working with them on their stories?

The most remarkable experiences I have had with teaching students to create and perform their own kamishibai is to see how it can bring even extremely shy kids out of their shell. When someone has spent a great deal of time creating and illustrating a story, they want to share it, and this becomes a strong motivation for overcoming stage fright. Also, because the cards are the focus of attention, the performer can take more of a backseat position. It is up to them whether they want to draw the audiences’ focus to themselves or keep it focused on the cards, and learning to direct audiences in this way is very empowering for young people and also a great skill to have!

You’re bilingual, and have traveled to Japan for both research and performances. What, in your experience, are some differences between kamishibai in Japan, and kamishibai in America?

One of the main differences I see is that many people in Japan have associations with kamishibai based on its sometimes troubling historical role, first as a street-performance art and then as a powerful tool for war propaganda during World War II. People outside Japan tend to romanticize the street-performance artists, but actually, they were not viewed at all favorably by many parents and educators at the time. The stories were considered violent and sensationalistic, much like video games today.

Kamishibai performers in Japan today continue to feel pressure to elevate the format and distance it from the negative aspects of its past. Since the war, the few publishers who still sell kamishibai tend to choose shorter and shorter stories for very young audiences, so kamishibai is increasingly viewed by people in Japan as a simple format only for small children. Of course, there are also many kamishibai performers in Japan who are trying to change people’s attitudes toward the format and forge new directions for the medium. Among tezukuri, or “hand-made,” kamishibai performers, you see stories of all genres and for all ages.

Outside Japan, performers don’t have negative associations, based on kamishibai’s past, but they do bring to the format their own cultural traditions. In Mexico, I saw many flamboyantly decorated stages, which I have never seen in Japan, and in Slovenia, I saw kamishibai used as a medium to perform songs and poetry. This is also something I have not seen as much in Japan.

Do you have a favorite kamishibai story?

I have many favorites, but, if I had to pick one, I think it would be “Nya-on, the Kitten,” illustrated by my dear friend Kyoko Watanabe. It is a simple story, but the sophistication of her design never ceases to amaze me. She is able to express changes in point-of-view visually by showing each scene from a carefully chosen camera angle, and the transitions from one card to the next are so clever. I use this story often, even with teenagers, to teach point-of-view in storytelling and how it can be expressed visually.

If you are interested in learning more about kamishibai, and possibly bringing it into your own classroom or library, Tara has written a book about this very subject (see below). It’s definitely worth checking out!

Used with permission of the author (Libraries Unlimited, 2010).

Literacy is, among other things, about communication. Writers write, readers read, and ideas and experiences are shared. Then I started thinking about communication in all its glorious forms. What about jazz music? Specifically, improvisational, free form, impromptu jams in which the musicians carry on entire musical conversations with their instrument voices. How exactly does that work? What cues are the musicians using? How do they know when to start? When to stop?

Literacy is, among other things, about communication. Writers write, readers read, and ideas and experiences are shared. Then I started thinking about communication in all its glorious forms. What about jazz music? Specifically, improvisational, free form, impromptu jams in which the musicians carry on entire musical conversations with their instrument voices. How exactly does that work? What cues are the musicians using? How do they know when to start? When to stop? At the program, Karen was joined by Brian Glassman on double bass and Tom Sayek on drums. All I can say is…wow. I can’t believe what they packed into that 60 minute performance.

At the program, Karen was joined by Brian Glassman on double bass and Tom Sayek on drums. All I can say is…wow. I can’t believe what they packed into that 60 minute performance. Karen explained accents, beats, syncopation, melody, tone, changes, coda, chords, tags, and pitch. Interspersed with her instruction were jazz pieces that not only demonstrated the concepts she was explaining, it also got the kids singing, clapping, and dancing along!

Karen explained accents, beats, syncopation, melody, tone, changes, coda, chords, tags, and pitch. Interspersed with her instruction were jazz pieces that not only demonstrated the concepts she was explaining, it also got the kids singing, clapping, and dancing along! At the end of the program, the kids were invited to come up and meet the musicians and the instruments.

At the end of the program, the kids were invited to come up and meet the musicians and the instruments. The drum set was an absolute mob scene.

The drum set was an absolute mob scene. But, as a former bass player, I made a beeline for the double bass. It was made in Concord, New Hampshire by Abraham Prescott circa 1820. Love. Loooove.

But, as a former bass player, I made a beeline for the double bass. It was made in Concord, New Hampshire by Abraham Prescott circa 1820. Love. Loooove. Later, I caught up with Karen to ask her a little more about jazz communication.

Later, I caught up with Karen to ask her a little more about jazz communication. You had a sneak peek

You had a sneak peek

Upon arrival, the kids were greeted by our “maidservant” (otherwise known as Anna, a sophomore at Princeton). Anna stayed in character the entire time. Let me tell you, she does an extremely authentic curtsy and fantastically demure “Yes ma’am.” She shares about her experience

Upon arrival, the kids were greeted by our “maidservant” (otherwise known as Anna, a sophomore at Princeton). Anna stayed in character the entire time. Let me tell you, she does an extremely authentic curtsy and fantastically demure “Yes ma’am.” She shares about her experience  When everyone had arrived, I was officially announced by Anna. I sashayed into the room, greeted everyone, and proceeded to do a 15 minute PowerPoint presentation on the history of tea in England.

When everyone had arrived, I was officially announced by Anna. I sashayed into the room, greeted everyone, and proceeded to do a 15 minute PowerPoint presentation on the history of tea in England. The historical content and connections for this program were quite extensive, and this post is already going to be rather long. So I’m going to describe the historical content in very broad brushstrokes. At the program, kids learned how tea was initially an expensive import available only to the upper class. It was also heavily taxed (sometimes over 100%). This resulted in a roaring trade in smuggled and adulterated tea. However, as tea became more affordable, it was enjoyed by all the citizens of England.

The historical content and connections for this program were quite extensive, and this post is already going to be rather long. So I’m going to describe the historical content in very broad brushstrokes. At the program, kids learned how tea was initially an expensive import available only to the upper class. It was also heavily taxed (sometimes over 100%). This resulted in a roaring trade in smuggled and adulterated tea. However, as tea became more affordable, it was enjoyed by all the citizens of England. To the dining room where our splendid tea table was laid out!

To the dining room where our splendid tea table was laid out! Waiting at each chair was a unique teacup and saucer. The kids got to take home these cups and saucers as mementos. They were so excited.

Waiting at each chair was a unique teacup and saucer. The kids got to take home these cups and saucers as mementos. They were so excited. The take-home teacup was something I really, really wanted to do when I first conceptualized this program. So I sent a request through our library’s

The take-home teacup was something I really, really wanted to do when I first conceptualized this program. So I sent a request through our library’s  I also stopped by Nearly New, a local thrift store/consignment shop. They completely hooked me up with some delightful cups and saucers.

I also stopped by Nearly New, a local thrift store/consignment shop. They completely hooked me up with some delightful cups and saucers. I couldn’t resist demonstrating tea pods as well. Have you seen these things? They are dried herbal pods you drop into hot water, and they “bloom” as they steep in the hot water. I first spotted one in Sophia Coppola’s movie Marie Antoinette. As luck would have it, Infini-T, our local tea shop, had them!

I couldn’t resist demonstrating tea pods as well. Have you seen these things? They are dried herbal pods you drop into hot water, and they “bloom” as they steep in the hot water. I first spotted one in Sophia Coppola’s movie Marie Antoinette. As luck would have it, Infini-T, our local tea shop, had them!

I was stationed next to the urn, offering milk and sugar. I can’t resist sharing this little history fact…way back when, sugar came in big cones you had to break apart with a special tool called sugar nippers. This resulted in irregular lumps of sugar. Hence the question “one lump or two?”

I was stationed next to the urn, offering milk and sugar. I can’t resist sharing this little history fact…way back when, sugar came in big cones you had to break apart with a special tool called sugar nippers. This resulted in irregular lumps of sugar. Hence the question “one lump or two?”

Having coached the kids on Victorian etiquette earlier in the program, I am happy to report that our young ladies and gentleman did very well indeed. Napkins were on laps, voices were not raised. We conversed very genially about their activities, interests, holiday doings, and travel adventures.

Having coached the kids on Victorian etiquette earlier in the program, I am happy to report that our young ladies and gentleman did very well indeed. Napkins were on laps, voices were not raised. We conversed very genially about their activities, interests, holiday doings, and travel adventures. To play “Hunt the Thimble,” have everyone leave the room except for one person. That person must hide a thimble somewhere in the room (however, it must be in plain view and not hidden behind anything). The players reenter the room and silently begin searching. If you spot the thimble, you immediately sit on the floor. The last person standing must pay a forfeit.

To play “Hunt the Thimble,” have everyone leave the room except for one person. That person must hide a thimble somewhere in the room (however, it must be in plain view and not hidden behind anything). The players reenter the room and silently begin searching. If you spot the thimble, you immediately sit on the floor. The last person standing must pay a forfeit. And now, for the crowning glory of the program. Joani, who is in Glee Club, agreed to research and perform some popular period music pieces. She sang two, including “How Doth the Little Crocodile.” The song is, of course, the poem from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland set to music. It’s from a rare 1872 Alice in Wonderland songbook from our special collections.

And now, for the crowning glory of the program. Joani, who is in Glee Club, agreed to research and perform some popular period music pieces. She sang two, including “How Doth the Little Crocodile.” The song is, of course, the poem from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland set to music. It’s from a rare 1872 Alice in Wonderland songbook from our special collections. We asked these kids to sit and look “proper.”

We asked these kids to sit and look “proper.” And check out the breeches on the young gentleman! I do believe those are modified baseball pants. That, my friends, is innovation.

And check out the breeches on the young gentleman! I do believe those are modified baseball pants. That, my friends, is innovation. But this “dress up” took the Wonderland cake. Behold the queen of hearts!

But this “dress up” took the Wonderland cake. Behold the queen of hearts! So how did the Victorian tea program go over? Amazingly well. Astonishingly well. We had a jolly good time I tell you! And while I loved the setting, the teacups, the costumes, and the cupcakes, the best part for me was how much history was packed in with the fun. Honestly, I don’t think any of them will ever look at a cup of tea in the same way again.

So how did the Victorian tea program go over? Amazingly well. Astonishingly well. We had a jolly good time I tell you! And while I loved the setting, the teacups, the costumes, and the cupcakes, the best part for me was how much history was packed in with the fun. Honestly, I don’t think any of them will ever look at a cup of tea in the same way again.