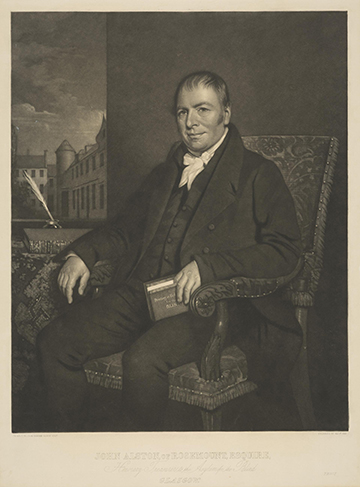

Alexander Hay. John Alston of Rosemount, 1778-1846. Hon. Treasurer of the Glasgow Blind Asylum. National Galleries of Scotland Collection. Photo, National Galleries of Scotland.

In today’s post, Katie delves into our special collections vaults and makes some very interesting connections! Let’s join her…

Sometimes doing research in the Cotsen collection feels a bit like the children’s book If You Give a Mouse a Cookie. I start looking for one title, which leads me to a different topic, and then I change directions entirely from what I was originally looking for. During a recent research excursion, I discovered Alston Type books, a new-to-me alphabet created in the 19th century to teach people who are blind or have low vision how to read.

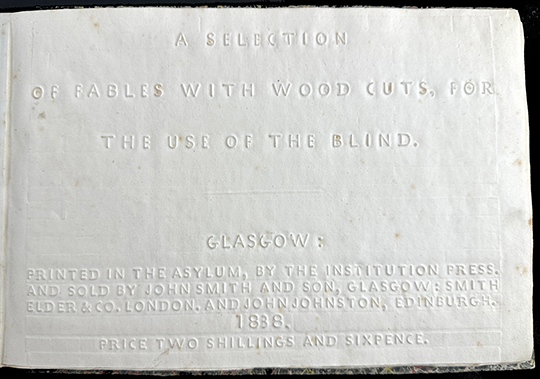

A Selection of Fables with Wood Cuts, for the Use of the Blind by John Alston (1838). The Treasures of the Cotsen Children’s Library Collection, CTSN 40903 Eng 18, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Everyone knows Louis Braille, who became blind as a young boy and invented his namesake alphabet in 1824 when he was a student at the National Institute for Blind Children in Paris. The braille alphabet consists of 64 characters, with each letter or number made up of raised dots in a certain pattern and embossed on paper. Today, braille is universally recognized as the common writing system for people who are blind or have low vision. Before braille was used worldwide, there were other tactile reading systems; some are discussed in a post written by Library Collections Specialist Charles Doran on Princeton University Library’s Special Collections blog.

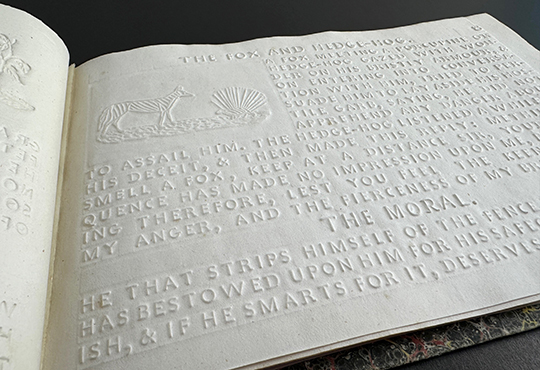

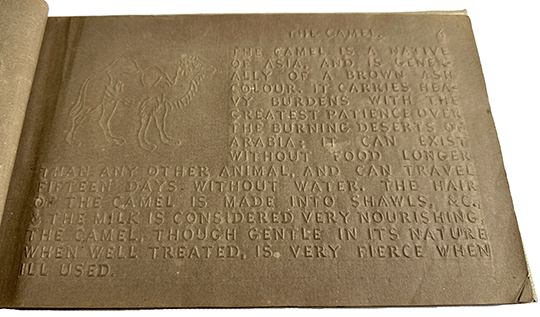

Another such system was created in 1837 by John Alston, who worked with the Asylum for the Blind in Glasgow, Scotland. Alston designed a raised font using the Roman alphabet in two different sizes: the smaller font for school-aged children and a larger version for older adults with a diminished sense of touch. Most of the Alston Type books were religious, but other topics included geography, music, natural history, and popular fables.

A Selection of Fables with Wood Cuts, for the Use of the Blind by John Alston (1838). The Treasures of the Cotsen Children’s Library Collection, CTSN 40903 Eng 18, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Alston’s desire was for every blind person in the United Kingdom to have an opportunity to read and learn from the Alston Type books. In a letter sent to directors of institutions throughout Great Britain, he stated: “The advantage to the Blind in having books printed for their use, in a distinct and tangible character is incalculable.”1 Alston was awarded a government grant to assist with printing and by 1844, more than 14,000 volumes were available for purchase. All of the sales proceeds were used to print more Alston Type books.

From A Selection of Fables with Wood Cuts, for the Use of the Blind by John Alston (1838). The Treasures of the Cotsen Children’s Library Collection, CTSN 40903 Eng 18, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

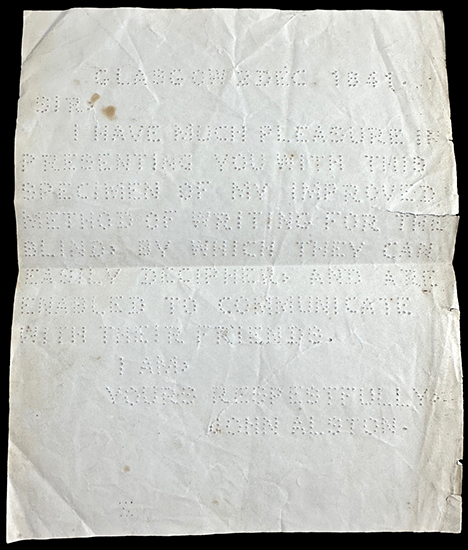

Glasgow 2 Dec 1841

Sir:

I have much pleasure in presenting you with this specimen of my improved method of writing for the blind, by which they can easily decipher, and are enabled to communicate with their friends.

I am yours respectfully,

John Alston

Children trained to read using Alston Type had a much easier time learning and reading other raised type books. Most importantly and due largely in part to Alston’s contributions, it was soon considered essential by all to provide formal education to people who are blind or have low vision.

Outlines of Natural History: Quadrupeds; Embossed for the Use of the Blind by John Alston (1842). The Treasures of the Cotsen Children’s Library Collection, CTSN 19486 Eng 19, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

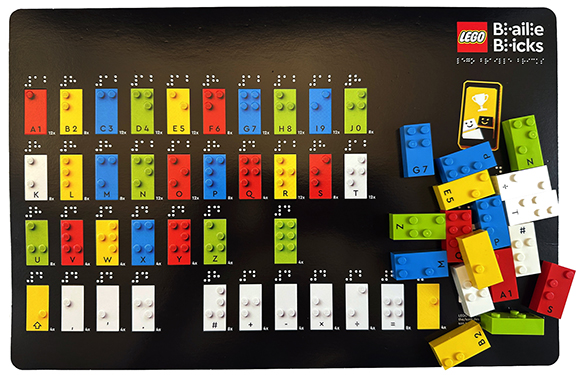

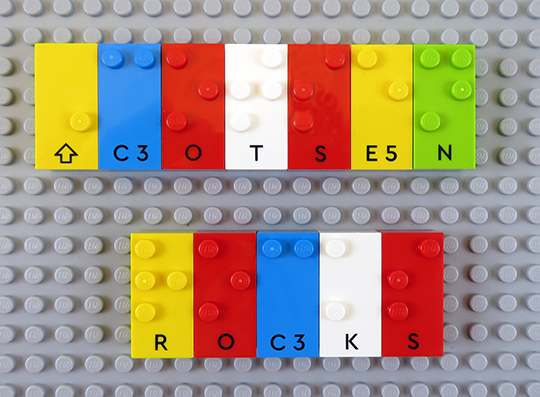

In a modern approach to inclusive education, LEGO introduced braille bricks in 2020. Along with a raised dot pattern on each brick, LEGO included the printed letter or character so sighted people could participate equally with the child who is blind or has low vision. There are multiple languages of braille bricks available for purchase, including French, Spanish, German and Italian.

LEGO. Play with Braille – English Alphabet. Set No. 40656 (The LEGO Group, 2023).

But the best part is the braille LEGO can be incorporated into all LEGO sets for additional ways to learn through play! LEGO also designed an online toolkit, The Braille Program, which provides professionals, teachers and families with courses, lesson plans, tips and tricks, and a multitude of ways to encourage playful learning.

Looking for picture books on this topic to add to your school or personal library? These titles come with our highest recommendation!

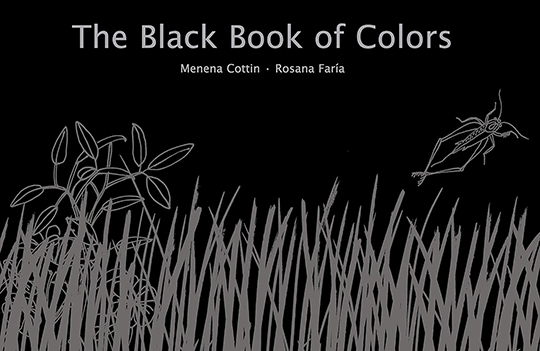

Image courtesy of Amazon UK

The Black Book of Colors by Menena Cottin and Rosana Faría (Groundwood Books, 2008) is a groundbreaking picture book written for children who are blind as well as children who are sighted. The entirely black pages throughout the book provide text in braille and printed white font on left, while the right-side pages have tactile raised line drawings of what the text is describing. It’s a beautiful way to challenge readers who are sighted to share the experience of a person who can only see by touch, taste, smell and sound.

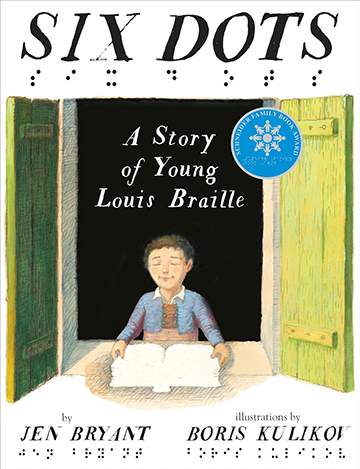

Image courtesy of Amazon

Six Dots: A Story of Young Louis Braille by Jen Bryant (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016) shares the story of Louis Braille’s childhood and how he overcame many obstacles and challenges to invent an alphabet for people who are blind that is still in use today.

1 John Alston, Letter to the Directors of the Institutions for the Blind in Great Britain & Ireland, 4 July 1837